Ride-sharing giants Uber and Lyft have attracted hundreds of millions of customers across the globe. They have done so by undercutting the price points offered by taxi companies. While taxis can still be cheaper than Uber and Lyft during “surge pricing” periods (when the supply-demand curve carries the price point higher), their best days are gone.

But now, Uber and Lyft are facing their own market disrupter, one that potentially poses a mortal threat to their business models. Enter Empower. It’s a recent ride-sharing market entrant that tends to be significantly cheaper than its older competitors.

BIDEN DISMISSES CONCERNS OVER LOOMING UNITED AUTO WORKERS STRIKE

Empower currently operates in North Carolina, New York, and Washington, D.C., but says it wants to expand. What makes Empower different from Uber and Lyft is that its drivers pay a subscription fee to the company in order to use its app. But after paying that fee, drivers set their own rates and receive 100% of the payment for each ride. In contrast, Uber and Lyft take steep commissions on each ride that its drivers accept. On its website, the company claims that “Empower is not a transportation provider like Uber or Lyft. Empower is a booking platform like Expedia.”

How much do Empower drivers pay to access the app?

It varies. But in D.C., for example, drivers pay between $49.99 and $449.99 per month depending on their earnings.

I’ve been using Empower for about a month now. I’ve found its service to be generally excellent. While the quality of Empower cars is sometimes of a lesser quality to those of Lyft and Uber, such distinctions are marginal. Empower drivers are also abundant in D.C., making for short wait times. More importantly, I’ve found that around 85% of the time, Empower rides are at least 15%-30% cheaper than Lyft/Uber rides offering the same journey. The drivers that I’ve talked to also seem far happier with Empower than they were with Uber/Lyft. They say they are earning significantly more with the new service.

Empower is not perfect.

Albeit rarely, its rides are more expensive than Uber/Lyft. In addition, while Empower offers a ride price estimate before a rider books, drivers can accept that ride at a higher price point. This makes it important for riders to quickly check that the accepted driver is charging a fee within the estimated range. And as with some Uber/Lyft drivers, some Empower drivers manifest the tedious tendency of accepting a ride and then driving off in the wrong direction in order to earn an easy cancellation fee. Unlike Uber/Lyft, however, I’ve found that Empower’s customer service is actually reachable. Emailing info@rideempower.com tends to get an effective response from an actual human being.

The underlying challenge for Uber and Lyft is simple. Namely, if Empower is earning drivers more money and saving riders more money, it may greatly threaten its competitors’ business models.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Uber and Lyft Still Allow Racist Behavior, but Not as Much as Taxi Services

LESSER OF TWO EVILS. The good news: Drivers for ridehail services such as Uber and Lyft discriminate against people of color less than taxi drivers. The bad news? They’re still not colorblind.

In June, the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) published “Ridehail Revolution: Ridehail Travel and Equity in Los Angeles,” a dissertation by Anne Brown, a doctoral student in Urban Planning. The paper examine how L.A. county residents use ridehail services and also includes the results of an experiment designed to suss out any differences in the way ridehail and taxi drivers treat passengers of different races.

BIG RACIST TAXI. For her experiment, Brown sent 18 UCLA students of various races to two locations in L.A. to hail rides, either from Lyft, Uber, or a taxi service. These students were all between the ages of 20 and 30, had ride-hailing app ratings of at least 4.5 stars, and wore “non-flashy clothes,” such as jeans and a t-shirt. Over nine weeks in the fall of 2017, the riders requested 1,704 rides from either a ridehail or taxi service.

Brown found that black ridehail riders had to wait 1 minute and 43 seconds longer than their white counterparts for rides and were 4 percent more likely than white riders to have their drivers cancel on them. Taxi drivers, however, appeared far more discriminatory — black taxi riders had to wait six to 15 minutes longer than their white counterparts for rides, and they were 73 percent more likely than white riders to have their drivers cancel on them.

CHANGES NEEDED. Brown appears to view the results of her experiment as a step in the right direction. “From an equality point of view, there’s some way to go before the gap between riders is truly erased, but it’s far narrower with ride-hailing, and with some policy changes, (Uber and Lyft) could erase the racial gap between riders entirely,” Brown told USA TODAY in June.

Still, the scope of Brown’s study was rather narrow — just one city with riders of about the same age — and other studies of ridehailing apps in other cities concluded that racial discrimination is far more prevalent than Brown’s study implies.

Regardless of which studies are the most accurate, though, they all seem to note some racial discrimination, and any racial discrimination is too much. In an effort to equalize rider treatment, Brown suggests that ride-hailing apps rethink how they identify riders, eliminating the practice of including a rider’s photo and name when they hail a ride.

Lyft and Uber, meanwhile, have long asserted that the identifying information is necessary to maintain driver safety. So unless they change their minds, it seems drivers will continue to have the opportunity to let their personal biases affect how long riders wait for their ride — if it ever arrives at all.

READ MORE: The Good and Bad of Ride-Sharing When It Comes to Race [Wired]

More on ridehail services: Driving for Uber or Lyft Is Awful, New Study Shows

The $1 ride that costs Metro $43. Why some want to keep it going

Ana Castro thumbs through her phone as the Metro Micro van pulls up next to her retail job at the Lynwood shopping center Plaza Mexico. Nervous about driving after her car was totaled and wary of traveling alone on the bus, the cheap ride-share service has been a lifesaver for the Watts teenager.

It’s clean, air-conditioned, picks her up near her front door and takes a fraction of the time it would to travel by bus to school or work. It’s like a Lyft or Uber ride-share with one huge difference: it costs a buck.

“Ever since I found this, I thank God,” Castro said. “I always use it.”

The rub is that while riders pay only $1 for the on-demand service called Metro Micro, the Los Angeles Metropolitan Transportation Authority pays about $43 per ride.

Public transit has always been heavily subsidized, but the cost is more than four times what it costs to provide a ride on a bus. The expense has rankled some inside Metro, which runs the pilot van program, and raised larger questions about service quality, fairness and the future of public transit.

A Metro Micro van cruises through Compton to pick up a passenger.

A Metro Micro van cruises through Compton to pick up a passenger.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

“It’s a money loser for Metro,” Los Angeles County Supervisor and Metro board member Janice Hahn said during a committee meeting last month.

The nearly 3-year-old, $31-million-a-year program is set to expire this month, but some are hoping to extend it or even make it permanent.

The program that started as an experiment in on-demand service has become an answer to gaps in Metro’s network.

Planners placed it in eight zones near 14 fully or partially eliminated bus routes. The vans can carry up to eight passengers and were intended to work for short trips in areas less than 30 square miles. But it has failed to attract large ridership even as a band of loyal users hail it a safe alternative to Metro’s train and bus system.

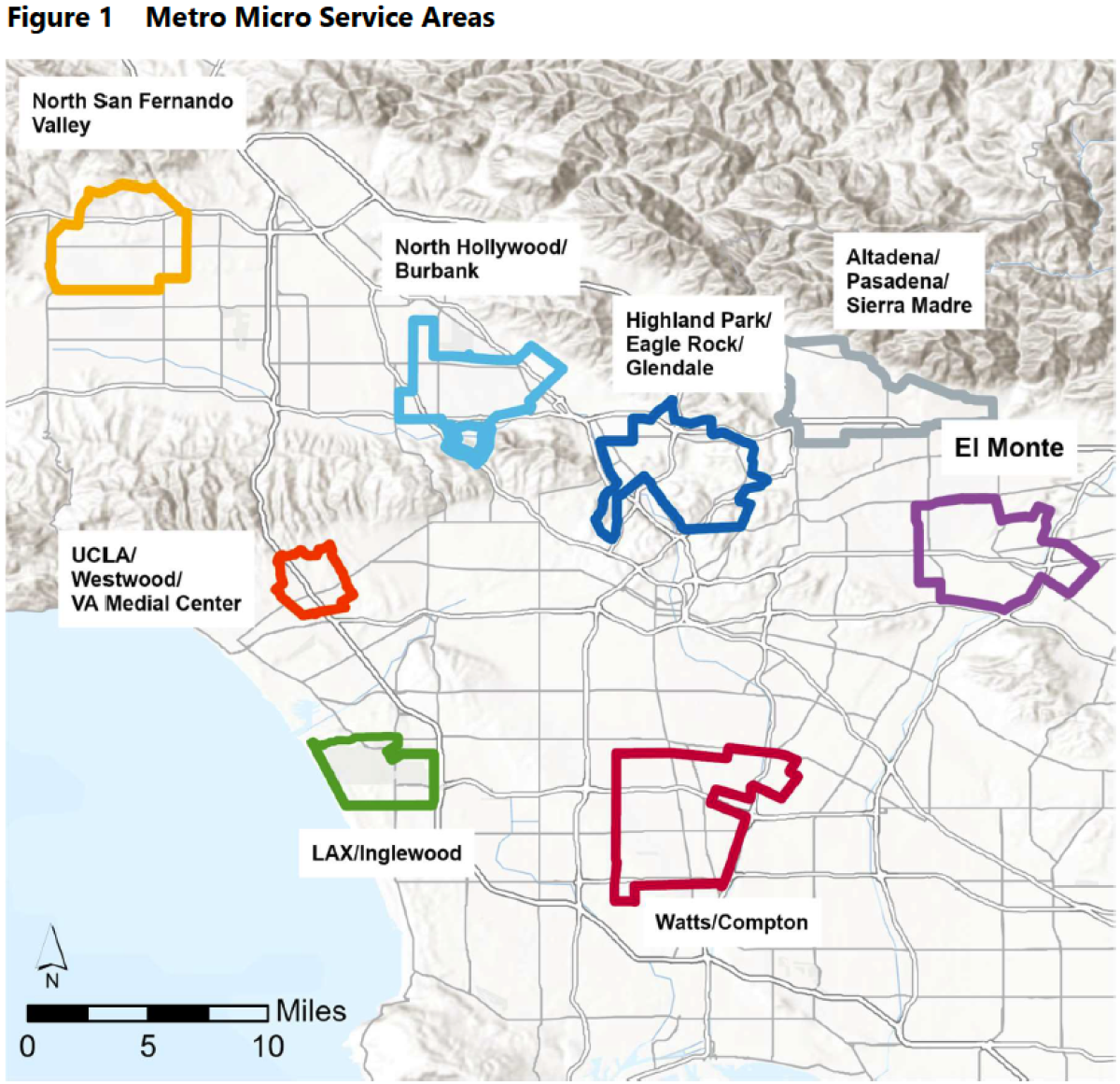

The Metro Micro operates in certain areas of Los Angeles, including eight zones near 14 fully or partially eliminated bus routes.

The Metro Micro operates in certain areas of Los Angeles, including eight zones near 14 fully or partially eliminated bus routes.

(Los Angeles Metropolitan Transportation Authority)

“I don’t really know what it gets us, except for we’re providing some rides, some dollar rides for people but it’s such a huge cost to do that,” Hahn said.

The biggest issue for Metro Micro is getting more passengers. Lower ridership drives up cost because it’s essentially becoming a personal ride instead of a shared one. Costs soared during its outset when weekday average rides were just 350 people and the cost to operate was $324 a ride.

“We’re learning our lessons in terms of what aspects we can bring down in costs,” said Conan Cheung, Metro’s director of operations. The agency is now looking at different business models, and trying to get rid of duplicative services in the program.

“It’s not going to be as efficient (as a bus),” Cheung said. “But it’s better service for people.”

The service has provided more than 1 million rides, and about 11% of the users surveyed are new to public transit, according to a Metro survey. The riders lean younger, and there’s a larger percentage of female ridership than on the bus.

Prem Gururajan, chief executive of RideCo, the fleet and software management company that Metro uses to run the service, said the program went through some growing pains.

“Metro did something that was first of its kind in the industry at this scale,” he said. “They’ve got a couple of lessons that we’ve been iterating on. They got a lot of things right. They’re moving really fast and learning to improve on those.”

The contract between Metro and RideCo was actually under budget, he said, adding that Metro has kept costs lower than other transit agencies.

“This is really the future,” he said.

Transit agencies from Washington, D.C., to Silicon Valley are trying out the taxi-like services that rely on software to connect riders to hard to get to areas. In places like the Indian reservations of Oklahoma or the mountains of Utah, the technology is being embraced because the service covers a larger area — going where traditional buses have not.

“I’ve been in rural transit for almost 20 years, and I’ve never seen anything like micro transit has done for us,” said Caroline Rodriguez, executive director of the High Valley Transit, which operates around Park City, Utah. “We are quite literally enabling employers to fill their vacancies because we have cut down the barrier to transportation.”

High Valley’s fare-free service largely caters to service workers who often live far from their work, she said. Many relied on pricey Ubers or just couldn’t afford to take jobs far from home.

In the city of Palo Alto, microtransit now does much of the work that discontinued community shuttles once did.

“It’s more expensive than a bus,” said Nathan Baird, transportation planning manager for the city. “But it provides a lot more additional access at an affordable price point.”

It’s a pivotal moment for public agencies still trying to recover from the pandemic and adjust to new commuting needs.

Metro’s program was launched in 2020 after federal dollars became available to experiment with on-demand service. Now dozens of Metro Micro vans offer near door-to-door transportation in eight regions of the county where low-performing bus routes have been eliminated. The service covers areas around Watts, Highland Park, Inglewood, El Monte, Sierra Madre, Westwood, Porter Ranch and Burbank.

Mismanagement marred the program early on as Metro squabbled over whether RideCo provided it adequate maintenance records. The Office of Inspector General found errors in invoices RideCo billed to Metro and excessive fees, and suggested that the agency look deeper into $2 million in insurance costs that may have been overcharged.

But in some ways, the service was a bright spot for Metro.

Ana Castro rides a Metro Micro van to her job in South Los Angeles.

Ana Castro rides a Metro Micro van to her job in South Los Angeles.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

The agency’s own surveys show users feel safer, arrive faster and feel more comfortable in the gray Micro van.

Castro said she doesn’t have to worry about men harassing her on the bus or while waiting at a stop, not far from her home. And she can call it early or late at night. “I feel more comfortable here,” Castro said.

While she talked on a recent ride, driver Alicia Price had the radio turned low playing R&B on KJLH. She lives in Watts and had been driving the vans for two years. During the school year, she said, the vans often filled up with students or people going to work.

There’s sometimes glitches in the software or maintenance is needed, but for the most part things run smooth and she enjoys the work, she said.

For years she drove buses for schools and the city, but it’s not something she wants to go back to, with recent stories of bus riders being stabbed, customers spitting and other indignities. She’d rather clean buses when nobody is on them.

“I am getting to this point in my life where I don’t got time for that,” she said.

She navigates through narrow streets in Compton, Watts and other parts of South Los Angeles that never see a bus.

By tracking demand patterns over a broad area, officials can identify the neighborhoods that need it the most.

Some complain that when there’s not enough vans, the app will not work. But Castro says she doesn’t encounter problems and rarely waits more than 15 minutes.

Those experiences matter and should be factored in when evaluating transit, said Susan Shaheen, co-director of the Transportation Sustainability Research Center, who has studied the issue.

“The quality of the trip is something that doesn’t get captured in fare-box revenues or in the number of passengers per hour or average cost per ride,” she said.

Only about 2,000 riders board Metro Micro vans on an average weekday compared to 877,000 bus and rail passengers — numbers which are still below pre-pandemic levels.

Critics say funding the vans is siphoning off regular transit users.

“There’s just not good evidence that it encourages folks to get on that micro transit service and connect to a passenger train on the other side,” said Chris Van Eyken, director of research and policy at TransitCenter, an advocacy and research group.

About 19% of riders go on to use Metrolink, a train or other form of public transit, surveys show.

“That money takes away from other things that can be done to improve bus service and increase ridership.”

The growth of these services has also hurt unionized work forces, he said. Some transit agencies use independent contractors to keep their costs lower.

“The opportunity to lower costs on micro transit would require sort of a race to the bottom in terms of labor,” he said.

But Joshua Schank, former chief innovation officer for Metro and a managing principal at the consulting firm InfraStrategies, points out that Metro Micro is unionized and that riders need better options.

“There should be a public alternative to Uber and Lyft that is sustainable and more affordable than Uber and Lyft,” he said. The micro transit program started in his office.

Schank lives in the San Fernando Valley, where a four-mile bus trip can easily turn into an hour-long journey.

“If I want to take transit somewhere, I gotta wait 20 minutes for a bus to show up and then transfer to another post, where I gotta wait another 30 minutes,” he said. “I could have done that in 10 minutes by car and it’s gonna take me an hour. To me, that seems unacceptable.”

Though the program was costly, he thought “it was worth it if it’s going to improve people’s lives dramatically.”

“The concern should be, are we using taxpayer money efficiently to provide necessary service to people who need it, and I would argue micro transit is a great way of doing that,” he said.